by Joe French

My dictionary defines collector as “a person who collects books, stamps, paintings, shells, etc., especially as a hobby.” I’d like to add to that: A real dyed in the wool collector is not happy until he obtains every item that has been made in a series of whatever he collects. At least that’s how it’s worked for me.

Miniature songbirds from Crowell’s list of 25 different species.

Heck Whittington gave us our first miniatures, a pair of his mallards, in the late 1950s. I don’t remember the exact date because, at the time, I was only interested in OLD HUNTING DECOYS, so I never bothered to make note of the date that I acquired them. Even though Heck was still alive, fortunately I didn’t exclude collecting his decoys since they had been made for hunters.

It’s the same with Charlie Perdew, who I tried to get to make me a pair of every species he had made, including wigeon. The older I get, the more I appreciate his stamina in his later years. Every time I went to his home in Henry, Illinois he wouldn’t “quite” have a decoy finished for me, but he always had a number of miniatures and game calls that he was completing on the dining room table. Twenty-twenty hindsight tells me how stupid I was to hold out for real decoys, but I was certain if I took some miniatures I would never get what I really wanted - hunting decoys. It’s only in the last few years that I’ve acquired several of Charlie’s tiniest treasures at auction.

Perdews miniatures are available, as are examples by many decoy makers, but no where near the extent of the four carvers who I decided to focus my collection upon: Robert Morse, Elmer Crowell, George Boyd and James Lapham.

Group of miniatures by Robert Morse. |

The second pair of miniatures I got was a pair of pintails on a piece of driftwood by Robert Morse of Ellsworth, Maine. I was shown a collection of them in Rock Island, Illinois, while scouting the Mississippi for decoys. They were so beautiful, I couldn’t resist getting at least one pair, so I called up our company salesman in Boston, who got them from the Audubon Society gift shop that sold all of Morse’s birds. I didn’t bother him again, as I was back on the track for real decoys. What a mistake that was! I’ve tried to correct that in the last few years, at much greater expense.

It was probably the decoy auctions that introduced many collectors to the miniature carvings of A.E. Crowell and his son Cleon of East Harwich, Massachusetts on Cape Cod. I don’t recall the onset of my downfall, but it was gradual, likely brought on by not finding much of anything at an auction. In the late 1980s, there were some great Crowell minis in a couple of auctions that I thought were priced decently. I was off to the races!

Elmer Crowell was born in 1862, during the Civil War, and died in 1952. He gave up cranberry farming and started a full time carving business in 1912 at the age of 50. His son Cleon (1891-1961) fought in World War I and began working full time with his father in 1920. He continued to run the shop after his father quit carving, due to arthritis, in the late 1930s. Cleon moved from the house next door to his father’s to Harwichport in 1946 and lived there until he died. He and his wife were in the real estate business and had other business interests, though he did continue some carving. The earliest known Crowell carving is a miniature Canada goose dated 1894. Some minis from 1903-1905 are in the Heritage Plantation collection in Sandwich on Cape Cod.

Shorebird hunting was outlawed, with the exception of plovers and yellowlegs, in 1918. In 1928 all shorebird hunting was banned. By this time ornamentals, especially miniatures, were an important part of Crowell’s business. Brian Cullity, the author of “The Songless Aviary: The World of A.E. Crowell & Son,” published for the Crowell exhibition at the Heritage Plantation of Sandwich in 1992, quotes Elmer as saying: “I don’t get much time to make decoys nowadays. The ladies keep me too busy making the small birds for them; there is better money in them, too.”

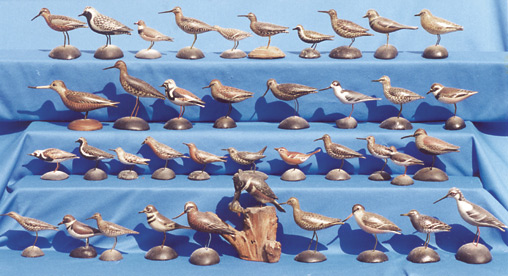

Crowell’s first sets of miniatures were offered in groups of twelve, increasing to 16, and ending up as a flock of 25. He made lists of the species with corresponding numbers for separate sets of ducks, shorebirds and songbirds. The number is often written in pencil on the bottom of the base. Many local schools acquired sets that were used as identification aids for the students. Occasionally an entire set of 25 will be offered at auction. With the help of Jim Parker, Steve Tyng and Ken DeLong, I managed to obtain copies of the three lists. You will also find Crowell miniatures not available in the sets. He was also willing to vary the set upon the request of the buyer.

In 1927 shorebirds and ducks cost $2.00 each, increasing to $6.00 in 1933, to $7.50 in the mid-1940s and $15 by 1959. A set of ducks, and I assume shorebirds, were $100 in 1930; a set of songbirds at that time was $75. Imagine how much money you could have made had you been there to order some. On the other hand, you’d probably be six-foot under by now.

Many, if not most, of the Crowell miniatures were marked on the bottom. The earliest ones have no brand or marking, followed by an ink stamp, a circular paper label and, lastly, a rectangular stamp, used exclusively after 1925, that was impressed into the wood. Often they were signed by either maker and dated, and some indicated the species and the name of the recipient, especially if it was a gift. Although Cullity indicates in his book that the timeline of the brands is useful in dating a carving, he suggests that evidence exists that the brands were often interchanged throughout their carving careers.

The author has collected a group of Crowell miniature shorebirds that are more than the 25 on his list.

George Boyd (1873-1941) of Seabrook, New Hampshire, was another old-time carver that made enough miniatures to satisfy many collectors. It’s a theory of mine that the ban on shorebird shooting, as well as the introduction of fibre, cork and plastic decoys, forced many decoy makers to look for other sources of income. It certainly applies to Geroge Boyd, because he started making miniatures, sold to sporting stores like Abercrombie & Fitch and Iver Johnson, shortly after the ban on shorebird shooting went into effect in 1928. He had sold only full-sized carvings previously.

Boyd was born in Seabrook and lived there his entire life. The local marshes were great for market hunting, a joyful pursuit for Boyd until he got married and took work at the local shoe factories. Yet he continued to hunt and make gunning decoys. The only known shorebirds are yellowlegs and plover, mostly black-bellied and a few golden. This has led many collectors to believe that the majority of them were made in the ten years between 1918 and 1928.

Like most carvers, there were certain characteristics of his full-sized and miniature carvings that make them easy to recognize at a distance. The heads on the shorebirds have a squarish look, a trait that carries to a lesser extent on the ducks. The heads on the ducks are more angular, opposed to the rounder symmetry of other carvers. And the look carries to the miniatures, which is amazing in that Boyd reportedly never used patterns for his carvings. Boyd inserted tack eyes in his miniatures, whereas Crowell painted them on.

Another deceased carver who made enough minis to satisfy collectors is James Lapham, another Cape Codder who was well acquainted with Crowell and his work. He was in the delivery service and often dropped items by the Crowell house. He was likely a happy-go-lucky sort, and maybe a little lazy. He was known to drive to the marsh, sit in the car waiting for a black duck to land, then get out and jump it. This ties in well with his being an avid bird watcher. Lapham’s wife fortunately worked in town as a waitress. When he got low on money, he would carve some birds and take them into town and sell them. He must have made a prodigious number, as one family has over 400 carvings, and you will readily find them available at auctions, especially those held on the Cape.

Lapham never made full-sized decoys, but he carved a great variety of wildfowl, including turkeys and wall mounted flyers, in addition to his standard ducks and birds. His miniatures resemble Crowell’s, especially in the rounded bases and carved clamshells, though he also used driftwood bases. His miniatures, larger than Crowell’s on average, have well-defined plumage patterns and his feather painting was more detailed and stylized. Most of the bases are signed in ink with James Lapham, Dennisport, Mass. and the species. Most are not dated. Some have a small oval brand with James LAPHAM curved at the top, BIRD CARVING in the middle and DENNIPORT, MASS curved at the bottom. He also used a rubber ink stamp on some that included his zip code of 02639.

As excellent as other miniature carvers may have been, they didn’t make enough birds to qualify in the categories previously discussed. Yet while they didn’t make sufficient numbers to allow many collectors to be able to gather a series of species, they are certainly worthy of space on your shelf. They include A.J. Dando, Frank Adams, A.J. King, Alfred Gardner and Harold Haertel.

Many decoy carvers made a handful of miniatures, so it’s always fun to latch onto at least one. Among those are Harry V. Shourds, Lloyd Tyler, Jess Urie, Heck Whittington and a few by the Ward brothers, whom I haven’t included above because their birds were normally bigger that mini size. George Starr made a few dandies too.

There are a number of miniature carvers who are happy to still be alive and not counted in any of the above groups. The most prominent that comes to mind is Ray Schalk of Clermont, Florida. Ray made many of those fantastic copies of the Mason factory decoys, both ducks and shorebirds, and now that he has retired from Proctor & Gamble, hopefully he’ll start making them again. His knowledge and technique were developed through intense study of the real thing, and he was a tremendous help when I was developing an article on Mason paint. The team of Bill and Becky Walker of Clinton, Pennsylvania make beautiful minis, and even though it’s a hobby, they’ve made a bunch. Captain Harry Jobes of Aberdeen, Maryland made “tons” of minis some time ago, but unfortunately you don’t find many today. A group of 50 or more is in the Havre de Grace Decoy Museum. But you’ll find examples of his son’s Bob Jobes minis at most of the decoy shows today.

And don’t forget there are some real beauties by Mr. Unknown, which could comprise a group of its own.

So good luck on starting a collection of miniatures. But as you try to add an example of every species produced, just remember there are still a number of those tiny treasures that I’m looking to add to my own collection.

For the complete story, please see the Jan./Feb. 2003 issue of Decoy Magazine.

Tidbits Main Index

|